This week, I had the opportunity to be in a lot of classrooms. In fact, by the end of the week I had worked in at least one classroom at every grade level, grades 6-12. To be able to witness the teaching of historical thinking at such diverse age ranges in such a short period of time is a gift.

I will probably reflect on the many great experiences in the coming weeks, but today I want to focus on one particular 9th grade class. In this class, students were exploring what life was like for Jewish people under Nazi Germany. They were engaging with one of our DBQs, guided by the prompt: “In what ways did the Nazis slowly change life for the Jewish people in Germany and German occupied land?”

Students learned in the previous class period that the Holocaust was not inevitable. They worked under the historical concept of contingency in order to recognize the specific actions of individuals and governments that slowly restricted Jewish life and allowed for their persecution, discrimination, and eventually, execution. When students recognize that the past is contingent on the people who lived it, it can bring hope. After all, if atrocities were not inevitable before, perhaps we can apply a keener eye to our present injustices in order to prevent them snowballing into something worse.

While I was there, we were able to go through various primary and secondary source documents that helped illuminate some answers to the prompt. Students began to make connections to how Nazi’s restricted Jewish life socially, economically, and politically.

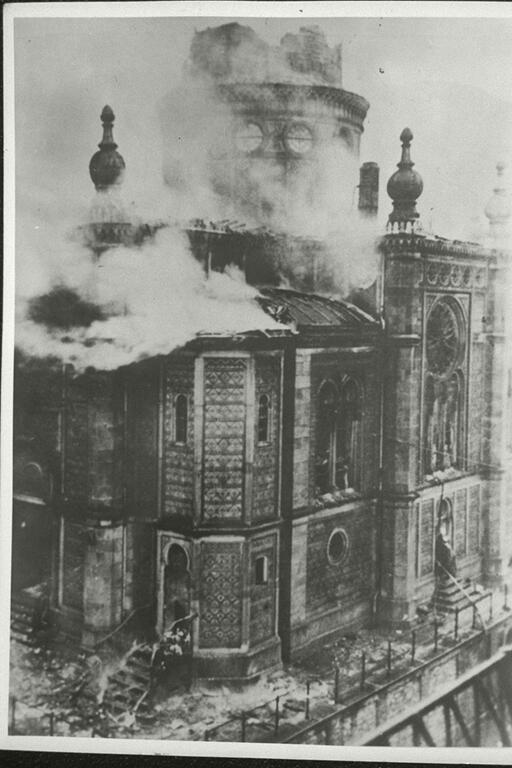

Students read the work of historians Saul Friedländer and Marion Kaplan. They analyzed a public announcement and a journalist’s picture that documented the social isolation Jews experienced early on when they were banned from public pools for “fear of contamination.” They wrestled with Joseph Goebbel’s diary entry where he applauded the atrocities of Kristallnacht. They empathized with a young girl who may have escaped the ghetto but did not escape the widespread persecution that awaited her outside the walls that consumed her sister. Students both analyzed and empathized in order to create their own argument about this time period. In short, they were asked to be historians.

At the end of class, the teacher and I thumbed through the exit slips, where the students could reflect on their learnings of the day. One of the questions was, “What surprised you in this lesson.” About half way through the stack of answers, I stopped and read one student’s response a second time. Then a third. Simply, she wrote, “I almost cried.”

In that moment, this student experienced the empathy that marks a good historian’s work. History was not merely “the past.” It came alive. This student engaged with the past in such a way where the past actors came to life. The statistics of atrocity bore a name, a story.

When we take the time to analyze the past and not merely remember it, it comes alive. Practicing these skills of historical thinking won’t just make us better students, but better people.