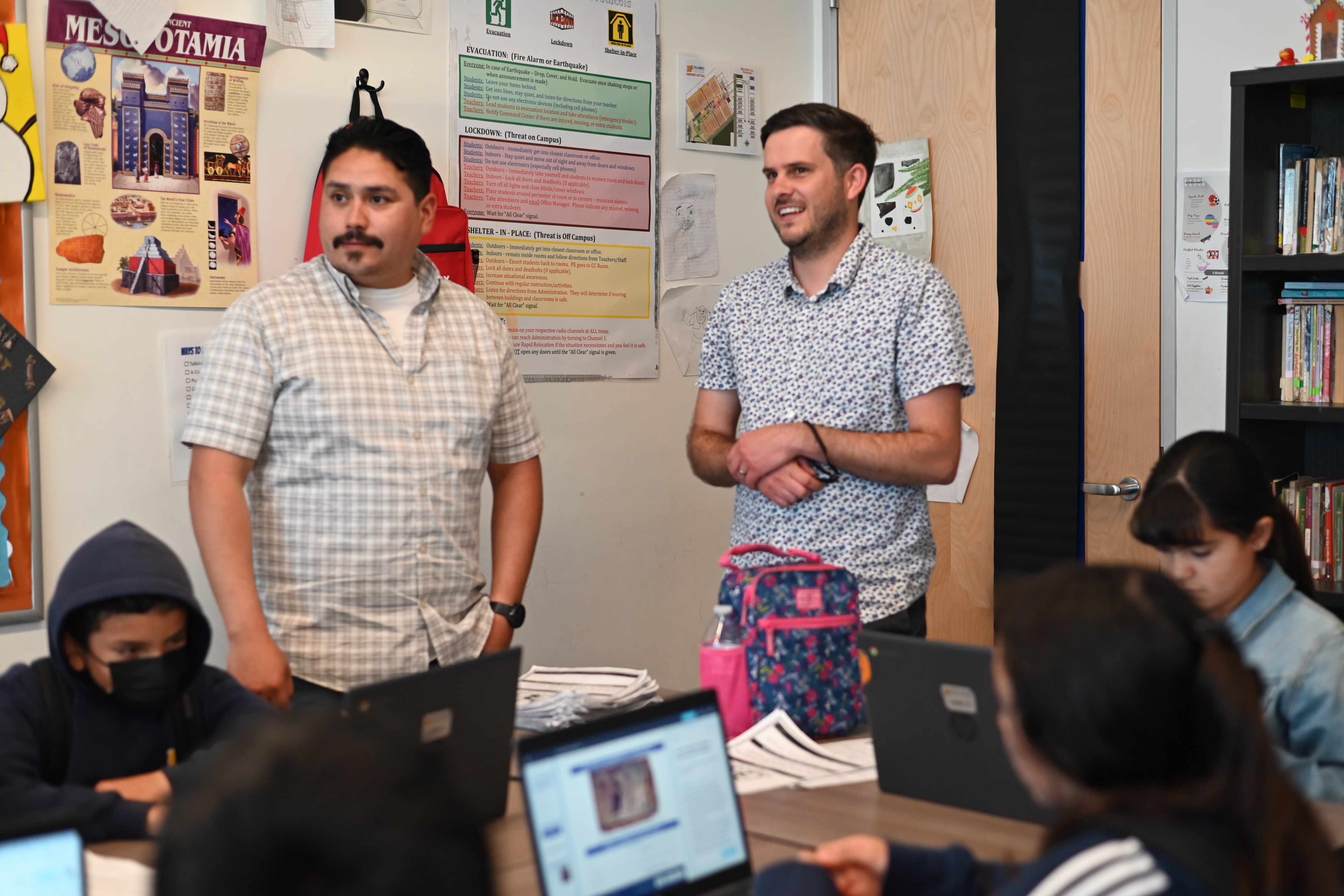

Thinking Nation's Collaborators

Why Partner With Thinking Nation

Promotes Literacy Development

Only 1 in 5 students is reading at grade level. Recent research found that literacy gains are more likely to materialize when students spend more time learning social studies. In fact, only social studies, of all subjects, made a positive, long-term impact on reading skills. Partnering with Thinking Nation ensures that your investment in social studies is also an investment in literacy development.

Develops Historical Thinking

Only 40% of social studies educators use the best practice of inquiry-based instruction at least once a week. Thinking Nation teachers center their classes on historical thinking, ensuring that a deeper, inquiry-based experience is the norm for all students. When students think historically, they are equipped to contribute to a flourishing democracy and thrive in an ever-changing world.

Professional Development

Fewer than 1 in 4 educators in the United States say their social studies professional development is very sufficient or excellent. Thinking Nation is changing that by offering high-quality, tiered professional development designed specifically for social studies educators. Our PD facilitates rich collaboration and vertical alignment, enabling teachers to deliver stronger, data-driven instruction.

Thinking Nation

As a nonprofit organization, we seek to empower students, support teachers, and transform social studies education for the future of democracy.

Curriculum

History is a discipline, not a content. Our curriculum aims to empower students through the development of historical thinking skills.

Our curriculum is historian approved! Thinking Nation asks expert historians to review our curriculum before it is used in the classroom. We believe that students should engage with history in a way that mirrors the conversations happening at the scholarly level. Also, by including expert historians in the curriculum-writing process, we can build a better bridge between secondary classrooms and the university.

Platform

Our platform houses hundreds of supplemental resources for upper elementary, middle, and high school teachers. Through their own portals, students can track their progress over multiple school years. On the homepage for teacher's portal, teachers can see real-time updates in student completion and grading status.

.pptx-Jun-25-2025-04-04-20-3879-PM.png?width=400&height=300&name=Thinking%20Nation%20Brainstorm%20(1).pptx-Jun-25-2025-04-04-20-3879-PM.png)

Resources

We want to support teachers the best we can as they empower their students to think historically. Our resources include our proprietary THINKS source analysis protocol, formative assessments, Socratic seminars, and curated-research papers (CRPs). Our CRPs are scaffolded more than traditional DBQs in order for teachers to meet all students where they are. Teachers can use these to teach a unit or as a summative assessment at the end of a unit.

Our rubrics are standards-aligned in order to facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration between social studies and English departments. We hope these samples help your students dig deeper into the topics they are studying.

Testimonials

“The students who take this will receive quite the education, so kudos to you and your colleagues for crafting such a thoughtful teaching tool. It is thorough, well thought out, and appropriate for this age cohort.” - Dr. Curtis Austin, Associate Professor of History, Arizona State University

“Thinking Nation meets the needs of all students by providing a diverse curriculum that captures their attention. Due to Thinking Nation, my students embraced the writing process, and their writing skills improved as a result.” - Christopher McCormack, High School History Teacher, Birmingham Community Charter High School

“In a world full of distorted historical interpretations, Thinking Nation became a light for my students to navigate the fog of misrepresentations. Thinking Nation helped my students become informed decision-makers by teaching them how to process a diversity of information and then using that information to generate college-ready essays.” - Jessica Guerrero, 10th Grade Teacher, IDEA Public Schools

Thinking Nation's Partners

Thinking Nation's Digital Platform

.pptx-Jun-24-2025-04-13-39-9614-PM.png?width=1024&height=768&name=Thinking%20Nation%20Brainstorm%20(1).pptx-Jun-24-2025-04-13-39-9614-PM.png)

Implement inquiry-based lessons and assessments that center historical thinking skills to provide a common language for measuring success.

Leverage generative AI on standards-aligned assessments that provide students immediate feedback and teachers usable data to enhance student thinking and literacy development.

Integrate effortlessly with your school’s LMS via Clever to manage every student and class account seamlessly.

Four-Tiered Implementation Model

Thinking Nation’s Four-Tiered Implementation Model empowers schools to build inquiry-driven social studies programs anchored in historical thinking. Each tier is carefully designed to guide schools from initial awareness to full integration, ensuring that both teachers and students dive deeply into the discipline. All professional development is tailored specifically for social studies educators and delivered by Thinking Nation’s team.

Historical Thinking Skills

All Thinking Nation resources are aligned to one or more of these skills!

.pptx-May-17-2025-09-25-31-2419-PM.png)