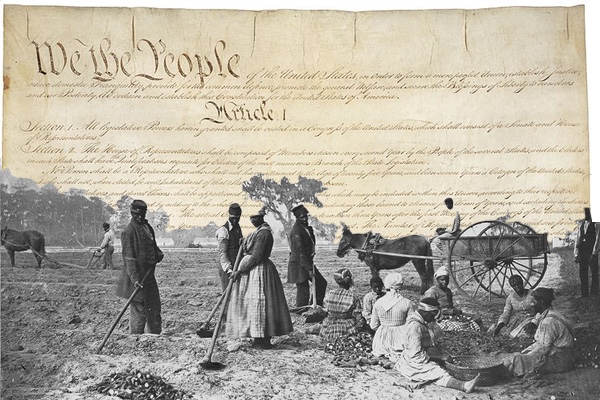

The creators of the United States Constitution set out on a difficult task. In creating a document to unify thirteen new states, while at the same time upholding those states’ sovereignty, the founders could not escape an inherent tension. Specifically, the issue of slavery coupled with the ideal of equality could hardly be reconciled.

In its preamble, the Constitution illuminates several actions of the “People of the United States” as a foundation to “form a more perfect Union.” Some of these actions are to “establish Justice, “insure domestic Tranquility,” “promote the general Welfare,” and “secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” This foundation upon which the rest of the document lays upon forces several questions: What is justice and for whom? Who is able to experience tranquility? Who falls under ‘general welfare’? Who’s liberty is secured?

Eventually, the nation’s stain of slavery would drip across this entire foundation and cause the Civil War.

Slavery is addressed three times in the 1787 Constitution. In Article I, Section 2, enslaved people are counted as “three fifths” of a person in regards to representation. This compromise kept southern states from garnering too much political power as they could have had if their vast slave population fully counted toward the amount of delegates they were allotted for the House of Representatives. In section 9 of the same article, the legal importation of slaves was given an end date, 1808.

Lastly, in Article IV, section 2, the Constitution stated that “No Person held to Service or Labour in one state, under the Laws thereof, escaping to another, shall… be discharged from such Service or Labour.” Known as the fugitive slave clause, this vague principle protected slaveholders’ right to pursue and retrieve an escaped slave, even if the fugitive made it to a state where slavery was abolished. It is in this last article that the preamble is put to the test. What was justice to a free-state may not be justice to the slave-state; likewise, “domestic Tranquility” could turn into domestic distrust if citizens within differing states chose not to cooperate. These inconsistencies between preamble goals and actual governance weakened America’s foundation.

Despite this visible crack in the new nation’s foundation, it appears that the framers of the Constitution saw no other way forward. They believed that abolishing slavery in the whole nation was out of the question if each of the states was expected to sign the Constitution. Not only did the southern states explicitly build their economy off of the backs of slaves, but as Thomas Jefferson noted, “for tho’ their [the northern] people have very few slaves themselves yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others.” The colonies had built an economy with slavery at its core, and if they wanted to create a new constitution in 1787, calling for slavery’s abolition was inconceivable to them.

Herein lies the deep paradox of our Constitution. Yes, as we at Thinking Nation believe, the principles of the U.S. Constitution are strong and enduring. We would do well as a country to adhere to them. Still, the Constitution is not sacred. It had significant flaws that deprived millions of Americans their personhood and allowed slavery to not simply continue, but to expand in the 70 years after it was signed. If we want to praise the principles of government outlined in our Constitution, we must, as many before us, condemn the errors that prioritized white compromises at the expense of black bodies.