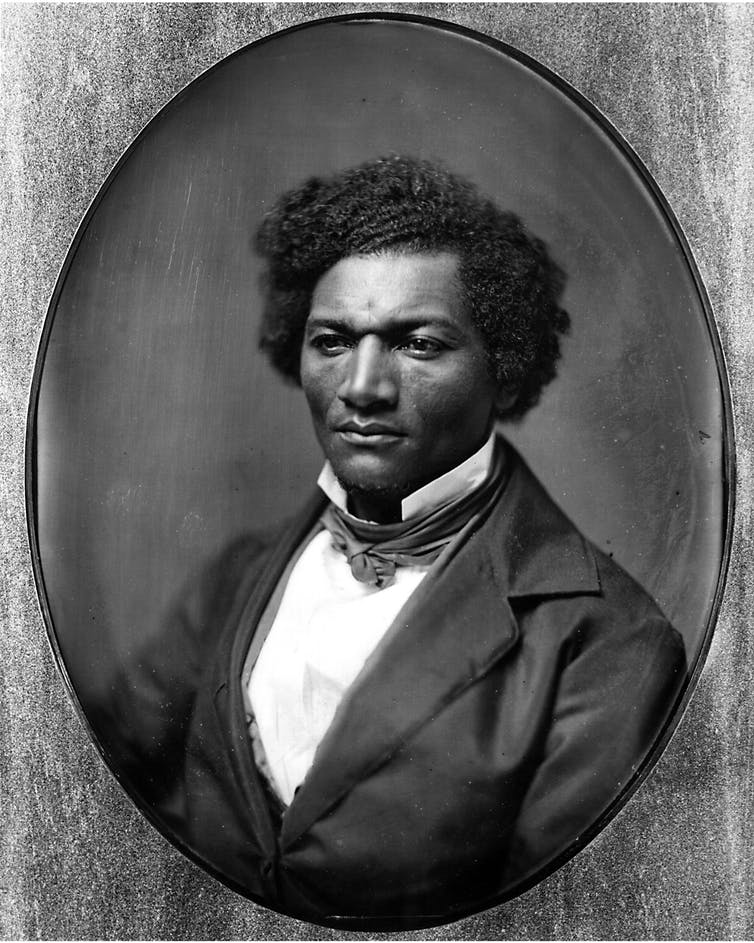

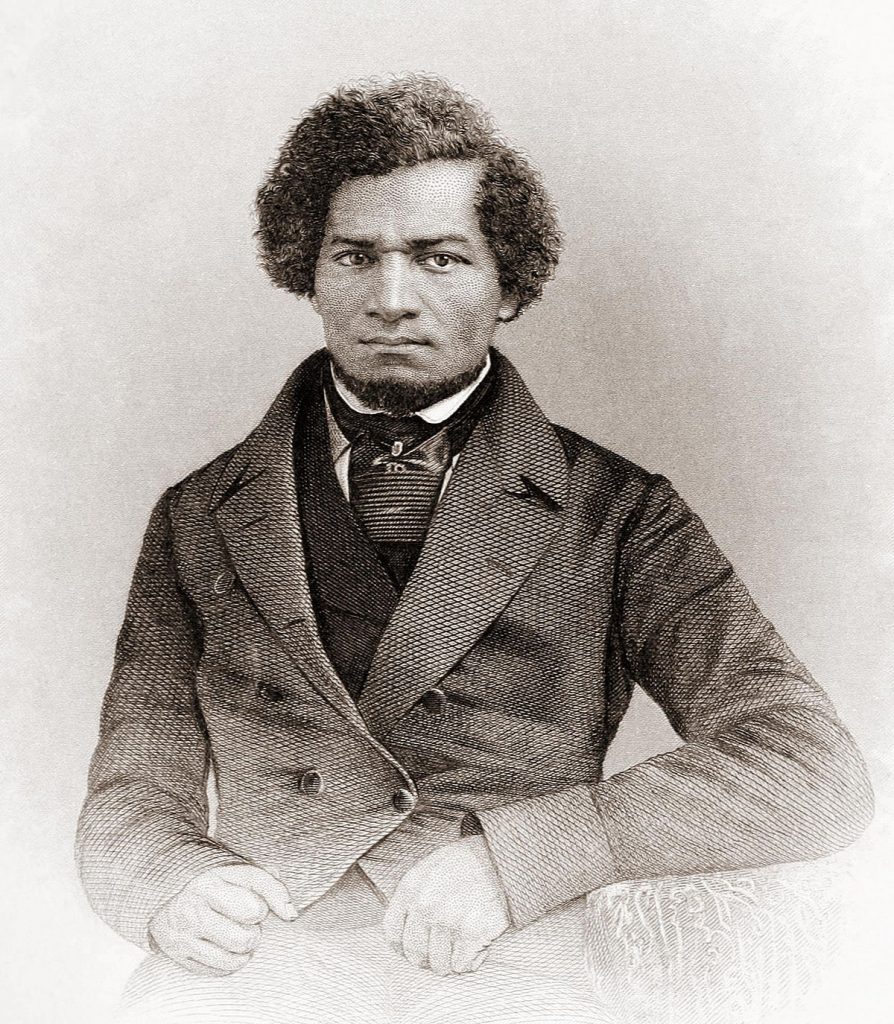

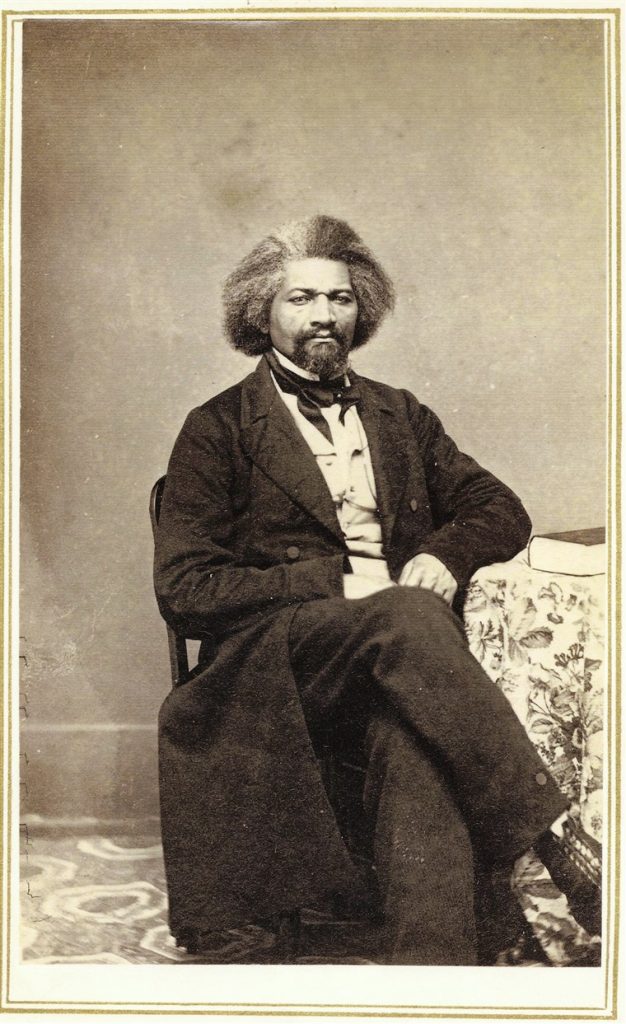

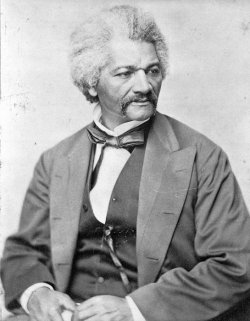

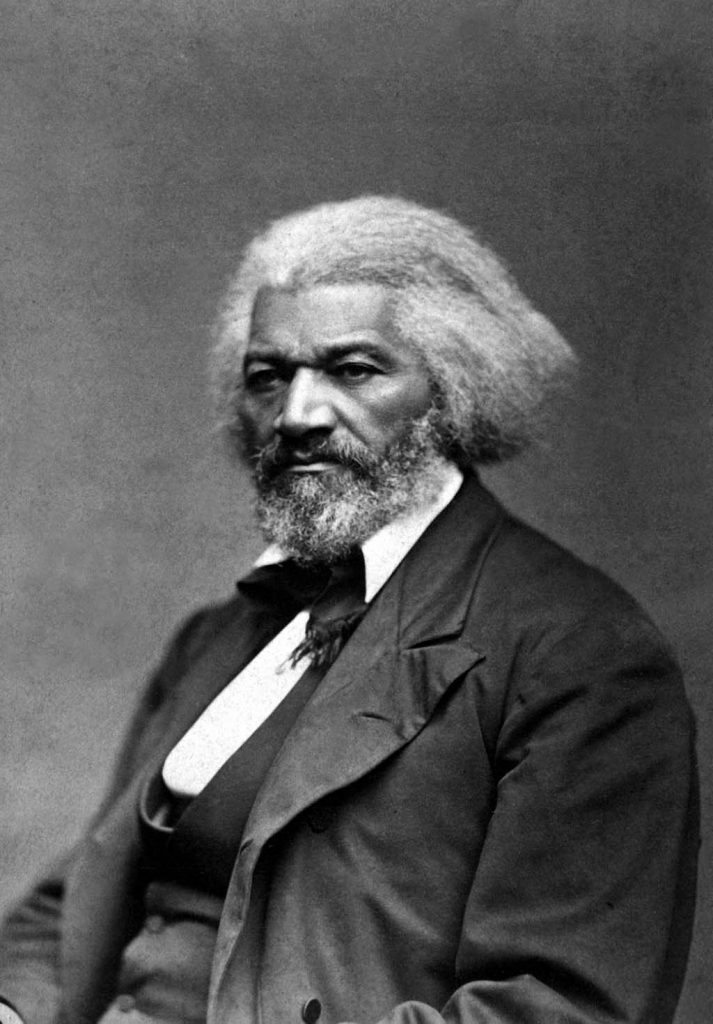

For those of us fascinated by Frederick Douglass, February is an especially important month. While he never knew his actual birthday, he celebrated it on February 14th. Then, on February 20th, 1895, Douglass died in the entryway to his home in Washington, D.C. Tomorrow is the 126th anniversary of the great abolitionist, orator, and writer’s death.

Frederick Douglass often appealed to the contradiction he saw in American society: a people who cherished their liberty but held millions in bondage. This theme spans decades of his work and is demonstrated in a variety of contexts. At the heart of his message was the idea that America was holding a double standard. The liberty and rights claimed for all Americans in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution were, in practice, only apportioned to white Americans, perhaps even only white men.

Shortly after his escape from slavery, and immediately after he returned from a two year time in Great Britain, Douglass was distraught. The very country that took away the liberty of the rest Americans treated him with dignity and respect. In his words, “I went to England, monarchical England, to get rid of democratic slavery.”

Throughout much of his writing, Douglass referenced the principles of the U.S. Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Among these principles, his writing emphasized that the government’s job is to protect the rights of its people. In 1847 he called for the “Constitution [to be] shriveled in a thousand fragments.”

In a different context, in his 1852 speech, “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?” he declared that “The principles contained in that instrument (the Declaration of Independence) are saving principles.” Interestingly, despite his stinging words against the Constitution in years prior, he affirmed what many of his white contemporaries would have agreed to—the principles of the Declaration of Independence were principles worth following. These principles he advocated to “be true to… on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost.” By 1852, Douglass had changed to believe that the Constitution was in fact an antislavery document. Then, he was not shy about calling out that Americans had not adhered to those principles. It was in this speech that he devoted most of his words to defending his observations “that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th of July.” Using the very occasion to celebrate America’s birthday, Douglass called his audience back to its founding principles, reminding them of the nation’s failure to uphold them for all people. Americans were not holding true to their goals, and Douglass felt it his duty to open their eyes.

Then, in 1865, in reference to asserting African American’s rights, he asked for “not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice” for “the colored people.” This justice found its basis in the “saving principles” of America’s founding documents. Douglass asked for nothing more than for these principles to be applied to African Americans, as they were White Americans. He wanted the simple justice of “the Negro’s right to suffrage.” It is here, too, that he decries America’s inability to extend this same right to women. Simply, and to applause, Douglass declared, “I hold that women, as well as men, have the right to vote.” The double standard of American liberty did not stop at the white-black dichotomy, but also between women and men.

Douglass would at times put forth the responsibility for change on his fellow African Americans, wanting them to ask themselves “What am I doing to elevate and improve my condition, and that of my brethren at large?” Still, it must be seen that he believed that until America reconciled its double standard of liberty, equality-for-all could not be guaranteed. America could not simply rid of this disparity by sending African Americans away. Throughout his writings and speeches, he called to action both white and black Americans to break down the splintered scaffolding that rested on the “saving principles” of America’s founding in order to rebuild a sturdy frame on a sturdy foundation. Because, after all, African Americans “are here and are here to stay.”

Douglass was an American hero. He chastised his country as a prophet and worked tirelessly to bring about real equality. He embodied historical thinking. We would do well to live in his legacy.