Last week, I read The Atlantic article, “The Big AI Risk Not Enough People Are Seeing: Beware Technology That Makes Us Less Human” by Tyler Austin Harper. His primary case, that AI must be used for human flourishing, is one that I have often made in AI circles the last year. Harper has recently been one of my favorite journalists to read. His cultural commentary consistently verbalizes things I’ve been thinking about in ways I couldn’t have done so effectively. I’m thankful to the Atlantic for prioritizing his writing regularly.

I want to take today’s post to dissect his claims a bit and also elaborate on how we take those claims seriously at Thinking Nation internally, as well as how we uphold the vision behind those claims in our collaborative work in the civics space. Generative AI has upended life as we know it, and it will only continue to do so. Not all upending is bad, though, so we must take into account how we use it in order to promote human flourishing. What we can’t do, as Harper so helpfully describes, is let it use us to detract from human flourishing.

Harper explores a space that we in the civics and history education space are perhaps not that up to speed in: online dating (disclaimer: I met my wife in HS, so have not had to navigate this space). In a growing “innovation” in that space, AI-run algorithms can weed out all the likely wasted first dates so that you can have the highest chance of relational success from the get go with the person you swiped right for. At its core, it’s a way to make the dating process much more efficient, but Harper points out the dehumanizing qualities that should really be the focus.

Harper marks the 20th century as one empowered by the onslaught of “disabling professions.” These professions took common skills to a community (medicine, schooling, child-rearing) and exported them to professionals. He calls these “disabling professions.” In some cases, such as medicine, this saved lives. But it also weakened human ability to cope with many aspects of life that had been inherent to human life for centuries (education) or even millennia (child-rearing). This “standardization and professionalization of everyday life” disabled normal human life.

In the 21st century, with the help of AI, these disabling professions were replaced by “disabling algorithms,” he argues. The latter being much more ominous for the future of humanity than the former.

He writes,

” Disabling Algorithms as tech companies simultaneously sell us on our existing anxieties and help nurture new ones. At the heart of it all is the kind of AI bait-and-switch peddled by the Bumble CEO. Algorithms are now tooled to help you develop basic life skills that decades ago might have been taken as a given: How to date. How to cook a meal. How to appreciate new music. How to write and reflect.”

Later in the article, he writes of the consequences of these disabling algorithms and how we need to have a clear understanding of our humanity to parse out the good algorithms from the bad. “We can’t take a stand against the infiltration of algorithms into the human estate if we don’t have a well-developed sense of which activities make humans human,” he posits. This is key.

CivXNow AI Working Group

Back in the fall, I had the opportunity to serve on a working group under CivXNow around the intersection of civic, social cohesion, and AI. My constant push in every meeting was that our conversations around the barriers we should set around AI are all irrelevant if we don’t have a common understanding of what it means to be human. Without first defining the ontological characteristics of humanity, any sort of walls around AI are too flexible, constantly adjusting to the whims of society at any given moment.

Harper addresses this need succinctly, “Without some minimal agreement as to what those basic human capabilities are—what activities belong to the jurisdiction of our species, not to be usurped by machines—it becomes difficult to pin down why some uses of artificial intelligence delight and excite, while others leave many of us feeling queasy.” If we don’t know what it means to be human, how will we know whether AI contributes to or detracts from human flourishing?

I had the opportunity to author the introduction and conclusion of the CivXNow Report that came out of our working group’s meetings. The report, titled “Unchartered Waters: Education, Democracy, and Social Cohesion in the Age of Artificial Intelligence,” gives some recommendations for how we can work together to ensure AI’s support of humanity, rather than its replacement. You can access some of the resources developed here.

In the introduction, I start with the famous line of the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…” as it sets a tone of human equality (and therefore some definition of humanity) that AI must must be seen in light of, especially in a civics space. My portion of the introduction ends with this, “As a community, we must be willing to honestly think through the various uses of AI and its implications in order to successfully wield its power without compromising our own humanity.” These discussions are imperative as AI becomes more ubiquitous in our daily lives. Otherwise, we don’t run AI, it runs us.

AI and Thinking Nation

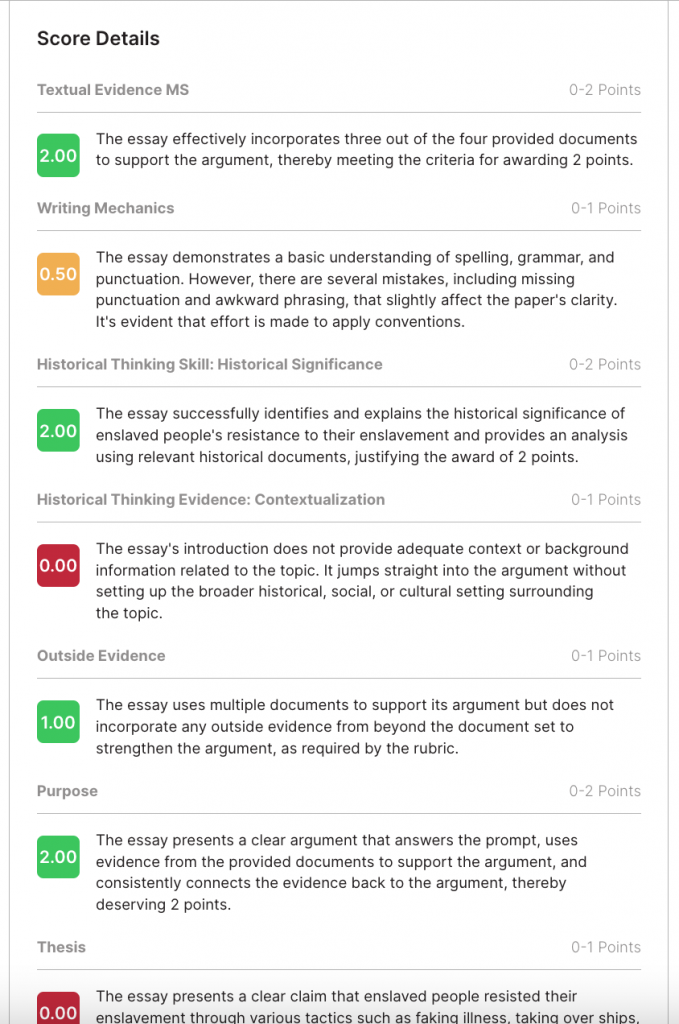

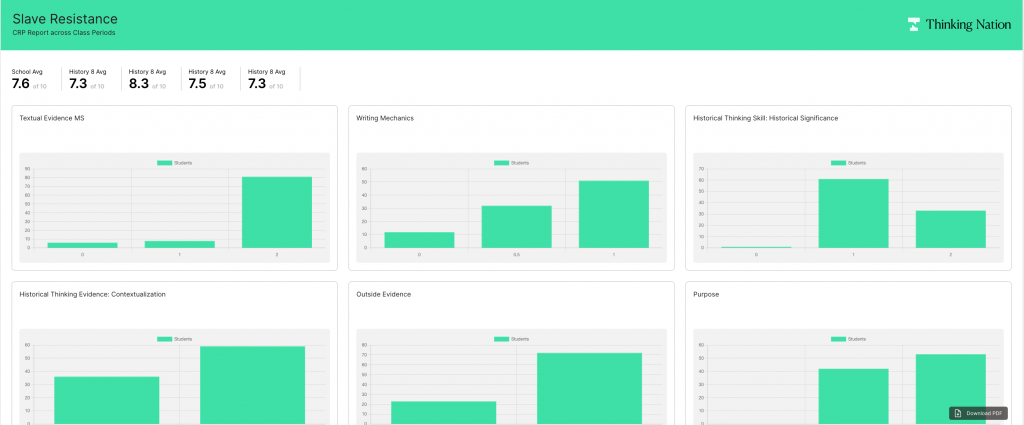

At Thinking Nation, we think deeply about how to use AI on our platform. Currently, we use it to grade student work to provide students with instant feedback and teachers with clear data on student growth. Since all of this feedback and data enhances the teaching of history as a discipline and better facilitates students ability to engage with the past, it also enhances their own flourishing. We incentivize this approach to teaching social studies because we know this way empowers students with the agency they need to actively engage with the world around them. There are many uses of AI that we choose not to entertain as it could cloud the difference between human and machine and blurry distinctions are no distinctions at all.

I was incredibly encouraged by Tyler Austin Harper’s piece in The Atlantic. He is calling our attention to the intense ramifications of AI that are hidden in the mundane aspects of our lives. This calling attention to is critical as we move forward in the age of AI. I’ll leave a portion of the CivXNow report’s conclusion here as I hope to continue the conversation around AI, human flourishing, and education:

“As leaders in the civics and education spaces, we know that just because something can be done, does not mean it should be. One of the core aspects of being a good citizen is to think about what is best for the community, not just oneself. At the core of that civic aim is really a question of our humanity.

As people, we are inhumane when we detract from human flourishing; we are humane when we contribute to it. These are the terms in which we should think as we consider how to harness the power of AI in a way that centers our own humanity and, conversely, how AI might be used in ways that lessens that humanity.”