In his research, Peter Seixas, professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia, outlined some key observations about history curriculums and teaching historical thinking that will serve as the baseline for today’s blog. Seixas oversaw Canada’s Historical Thinking Project, a federally funded curriculum project that sought to reorient Canada’s history education toward historical thinking. What they produced was illuminating and the United States would do well to focus their attention on something similar.

Seixas and his colleague, Carla Peck from the University of Alberta, write that history curriculums are often presented in one of three ways: as a way to teach a nation-building narrative, to analyze contemporary events in historical context (social studies), or as a discipline of inquiry focused on historical thinking. Despite these three approaches to history education, the general public usually only associates history education with the first: nation-building.

Our current culture wars are a perfect example. On one hand, many Americans see a waning respect for our country and believe that the history classroom must reinvigorate this respect by telling stories of American greatness. The 1776 Report commissioned by former president Donald Trump is a prime example of this. On the other hand, many other Americans hope to decolonize the history classroom by replacing white settler-dominated narratives with stories of oppressed groups, indigenous nations, and people of color. History from the bottom up as they say. Both of these fit the narrative of nation-building even if they dramatically differ on what type of nation they want to build.

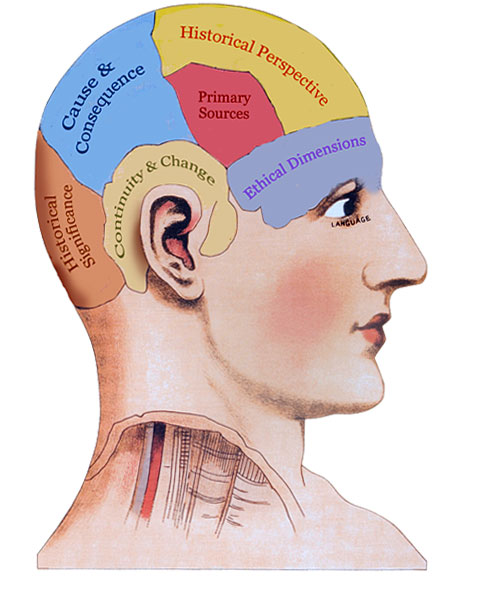

But centering history education into the middle of this debate misses the point of history education. History, as we’ve noted time and again, is not the past, it is the study of the past. So teachers of history should be teaching how to study the past, not just the past. When history education becomes about the narrative it tells, we’ll endlessly debate questions about which story to tell instead of equipping students with the skills of historical thinking.

Thinking Nation’s curriculum rises above this politicization of the history classroom by focusing less on which story to tell and much more on the modes of inquiry inherent to historical thinking. Even though teachers are stopped and asked “Do you teach CRT?” by people who cannot even define the theory itself, we only play to the political game by entering these debates. It becomes about proving our allegiance rather than educating children. As a discipline, we can rise above the partisan narratives by teaching history as a discipline and not a synonym with “the past.” We can equip our students with tangible skills of analysis instead of assuming that our chosen narrative of the past is superior to all others.

We want to work with schools aren’t looking to adopt curriculums merely to please their chosen political tribe, but who want curriculums built with the students in mind. Schools who want to facilitate real learning, the deep thinking, or paideia that the great scholar Cornel West so often reminds us is the purpose of education.