[This blog was adapted from a previous Thinking Nation blog on May 28, 2021]

The month of May is AAPI Heritage Month, or Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. We want to take this week’s blog to honor those who resisted injustice and persisted toward equality within the AAPI community. This week’s blog will highlight three instances where Asian Americans called the United States to live up to its founding ideas of liberty and justice for all. Each of these stories come from our curriculum’s library of DBQs and we hope that as you engage with their heroism today, students will engage with their stories in the classroom.

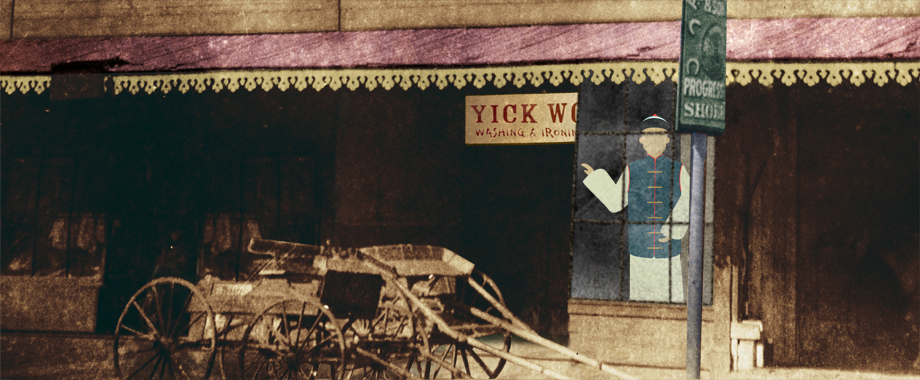

Our first story of resistance and persistence comes from San Francisco in 1886. Chinese men Yick Wo and Wo Lee were denied permits to operate their laundry businesses under a new discriminatory law in San Francisco. While the law did not mention race at all, after the city council passed it, only white laundry business owners could obtain permits to legally operate in the city. Yick Wo and Wong Lee challenged this discrimination on the basis of the relatively new (passed in 1868) 14th Amendment, which states, “No State shall… deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” To put the amendment to the test, they continued to operate their businesses without permits, and then when threatened by the city, made their case in the U.S. legal system. Despite the new city law not explicitly referencing Chinese San Franciscans, Wo and Lee took their case (Yick Wo v. Hopkins) all the way to the Supreme Court to argue that the city’s laws violated their 14th amendment rights. The court unanimously sided with Wo and Lee and set a profound precedent in U.S. legal history. The court argued that just because a law is not racist on its face doesn’t mean it can’t violate a citizen’s 14th Amendment rights. Their resistance and persistence led to an important change in our justice system. (Here is a free document analysis activity highlighting the court case).

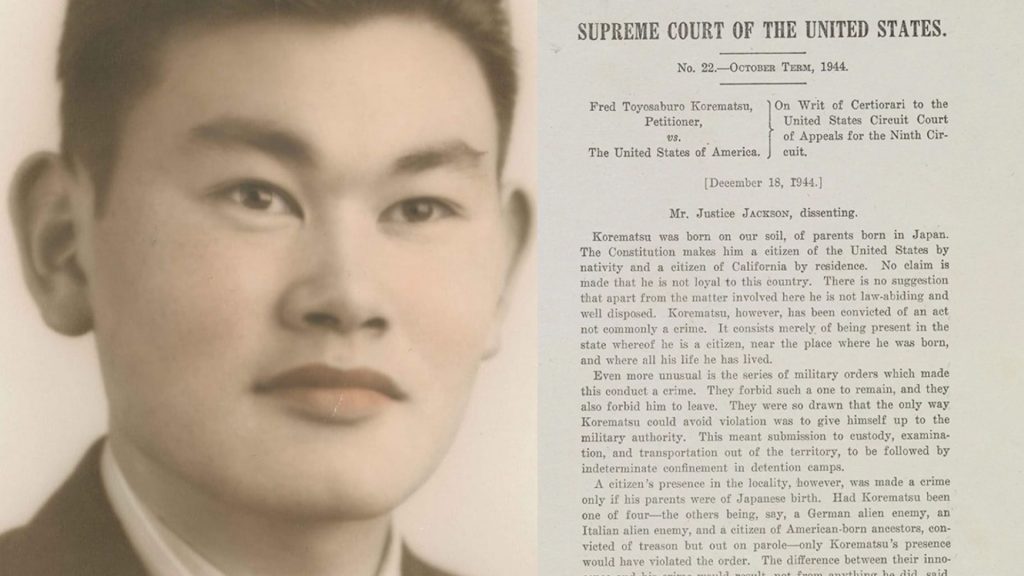

Our second story to highlight during AAPI Heritage Month comes during the American tragedy of Japanese internment. During World War II, the American government forced Japanese Americans out of their homes, rounded them up, and forced them to live for almost three years in concentration camps in remote areas mostly in the Western United States. Resisting this unjust internment, Fred Korematsu hid in Oakland. He was later arrested and jailed for refusing to be taken from his home to one of these camps. The ACLU used his arrest as an opportunity to test the legality of Executive Order 9066, which President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed to intern Japanese Americans, arguing that it was in the interest of national security. Sadly, the U.S. Supreme Court did not uphold the 14th Amendment rights like it did in 1886 and ruled 6-3 in favor of Korematsu’s conviction. Still, Korematsu paved the way for America’s apology for this atrocious act against Japanese Americans. In 1982 a federal commission found that the Executive Order was shaped by “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” In 1988, the government paid $20,000 in reparations to each surviving internee. Korematsu’s resistance set the foundation for justice.

Our third story takes place in 1965. Thousands of Filipino farmworkers in California were working underpaid and in inhumane conditions in California farms. Filipino-native Larry Itliong, who led the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) led a successful strike in Coachella to raise the wages and working conditions of Filipino farmworkers. From there, the workers followed the grape crops to Delano, CA. When refused the same wages they were granted in Coachella, they planned another strike. But to avoid Mexican workers taking the jobs once the Filipinos went on strike, Itliong approached Cesar Chavez, the leader of the association that primarily served Mexican farmworkers. Initially hesitant, Chavez agreed to help Itliong and join the strike. This became the great Delano Grape Strike that lasted 5 years and became an international movement to advocate farmworker rights. If it were not for the resistance and persistence of Larry Itliong, the movement would have never come about.

During AAPI Heritage Month, may we remember the contributions of the above three men and so many more within the AAPI community who resisted injustice and persisted toward equality on behalf of Asian Americans throughout the United States.