[A quick note: It was so great to meet so many of you at the California Council for Social Studies conference this past weekend. I loved hearing so many inspiring stories at our booth and sessions!]

This is the week!

I feel like the phrase “now more than ever” is a perennial favorite in the civics community. But perhaps it is because the time is always ripe to practice civics. Civics goes beyond knowledge of the government. It is a worldview that we can collectively exercise to both strengthen our democracy and our society. Civics Matters.

In this 3rd annual Civic Learning Week, orchestrated by our friends at iCivics, I wanted to take the time to reflect on what Civics education means in Thinking Nation classrooms.

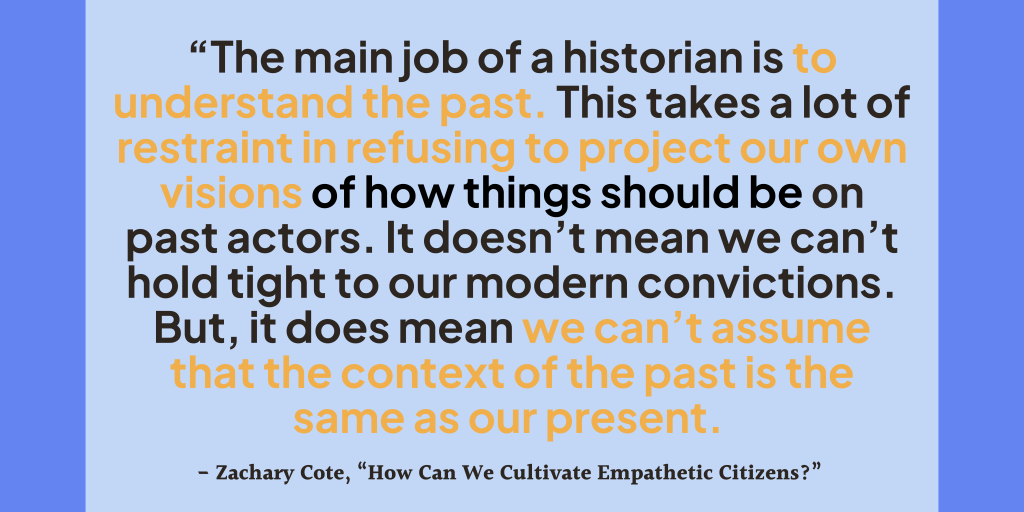

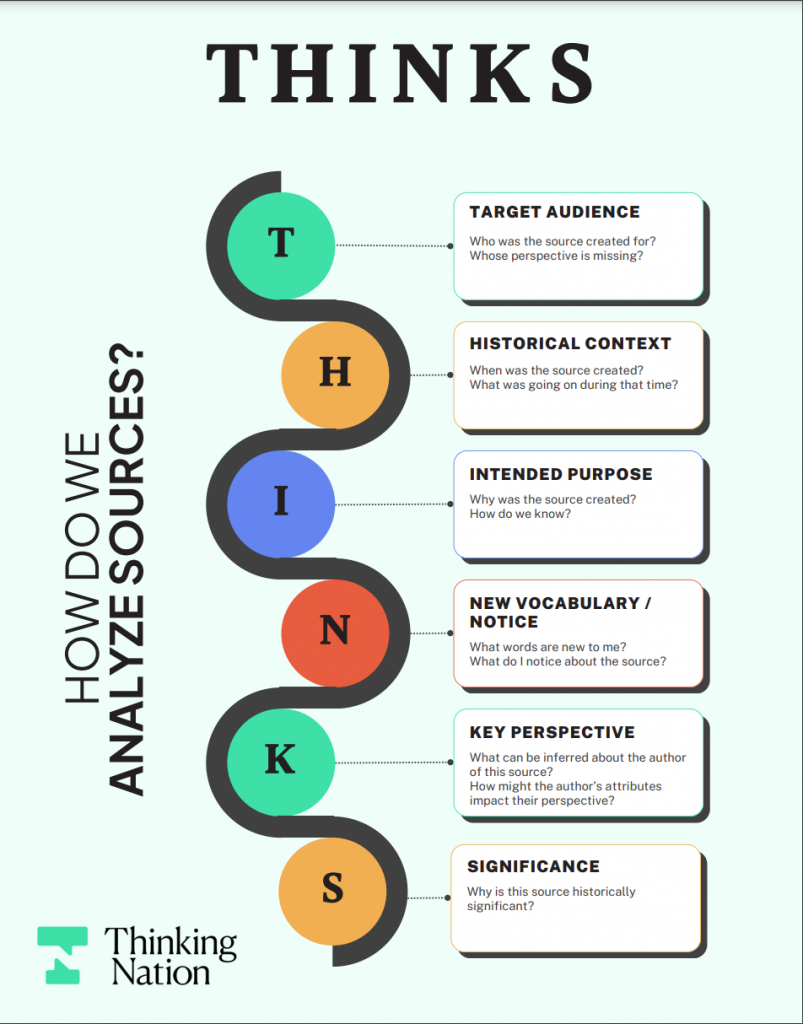

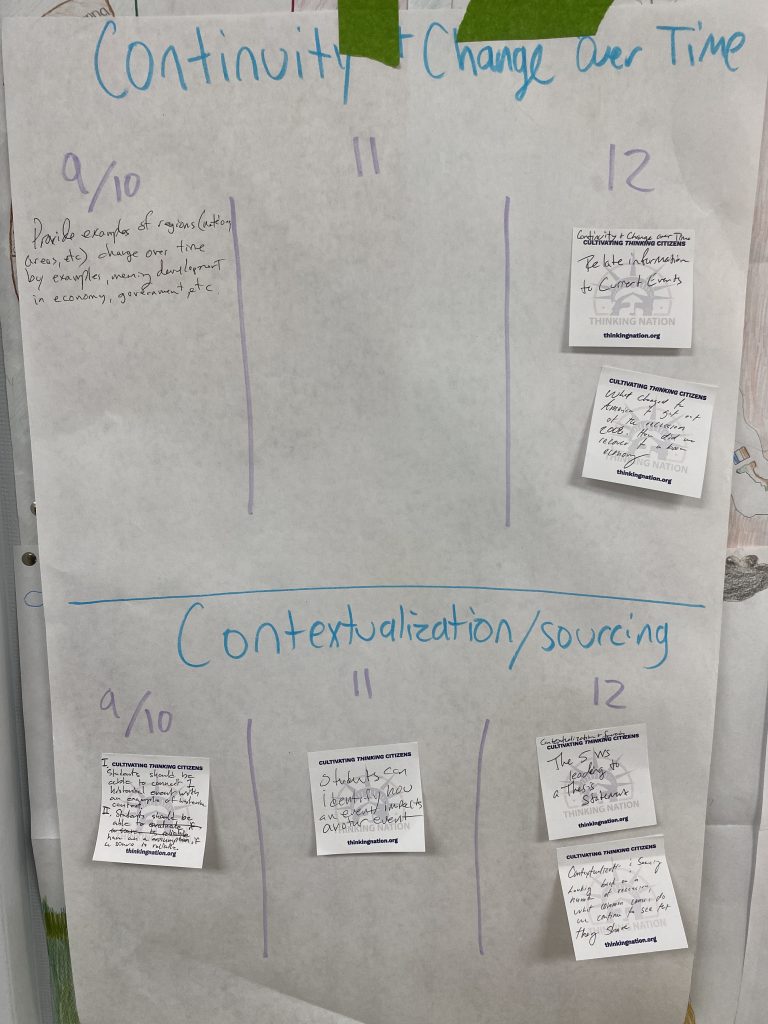

As I wrote awhile back, I believe that a quality history education is an exercise in civics. When we teach history, we are equipping students with valuable dispositions that transcend the classroom. When students practice historical empathy they are utilizing essential skills for understanding their neighbors and the diverse perspectives they encounter. They can apply the same skills used in contextualizing past events when they are better trying to understand the context of our time. When evaluating evidence in primary sources, they are internalizing questions that we must ask about present sources if we want to be media literate. I could go on.

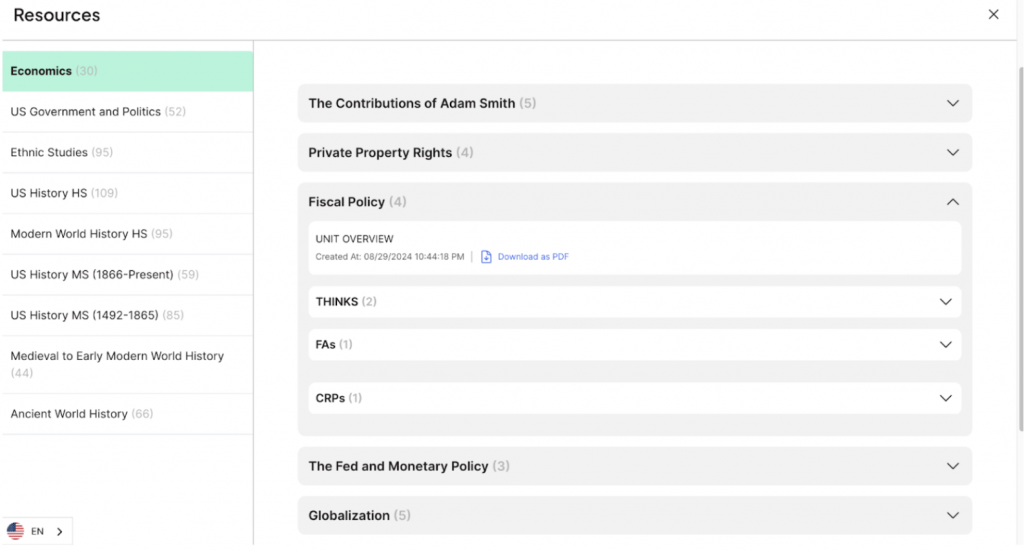

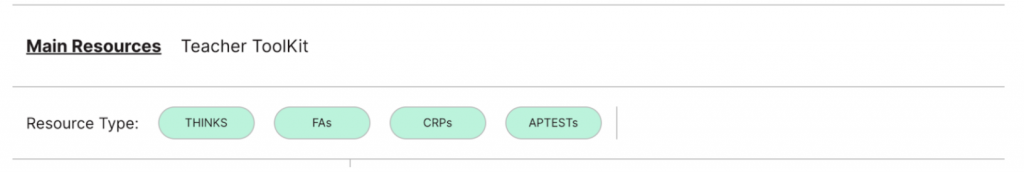

Historical thinking empowers students to be the citizens our society needs if we want to preserve and protect our constitutional democracy. As I reflect on what this means for us at Thinking Nation during Civic Learning Week, I want to take a moment to thank some teachers who are doing this in their classes.

Shouting Out Our Teachers!

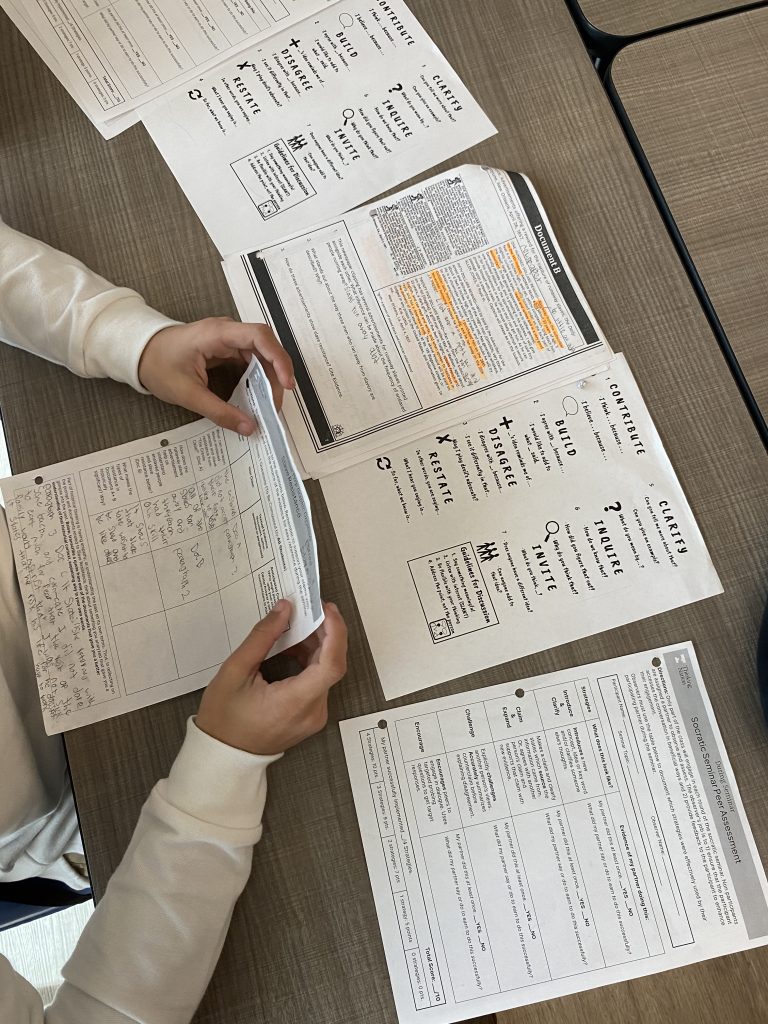

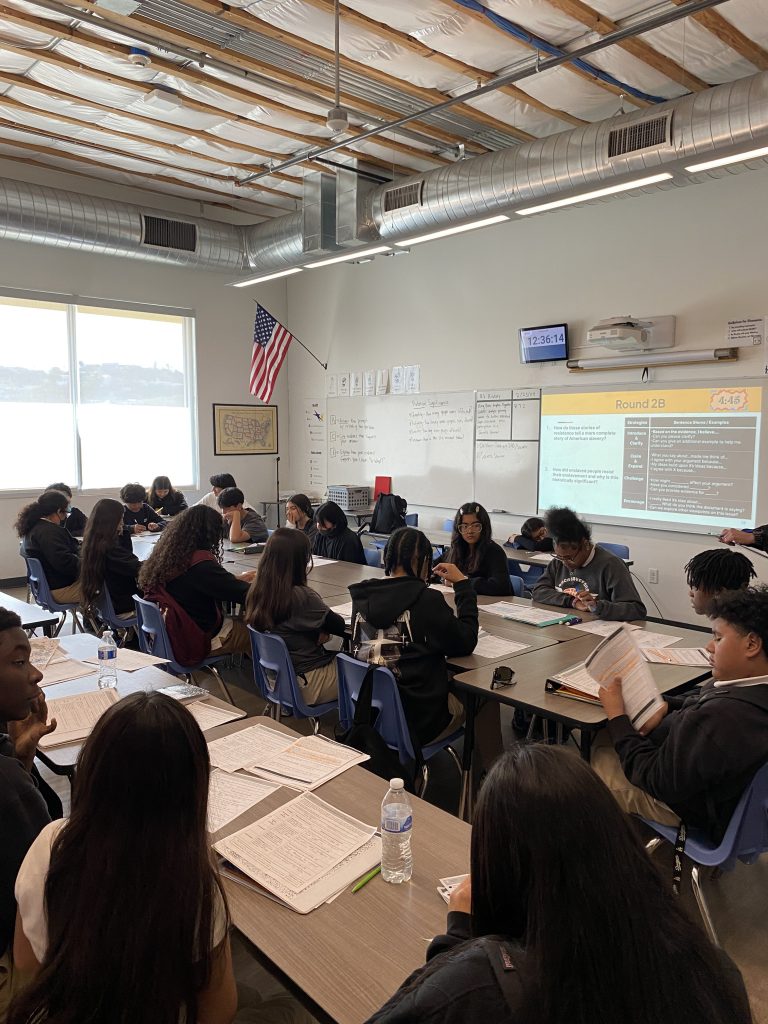

📣 Shout out to Mrs. Mayra Brady at Cabrillo Middle School in Ventura, CA! Mrs. Brady had her 6th graders engage in a socratic seminar using primary sources from Confucianism and Daoism. During the seminar, students challenged one another to think critically about similarities and differences between the philosophies, pushing one another to cite evidence to support their claims.

📣 Shout out to the social studies department at Birmingham Community Charter High School in Van Nuys, CA for creating vertically-aligned goals around student thinking using student writing data. I’m grateful to Dr. Carlo Aaron Purther, the department head, for putting the needs of teachers first so that they can put the needs of their students first. The resulting student growth is admirable.

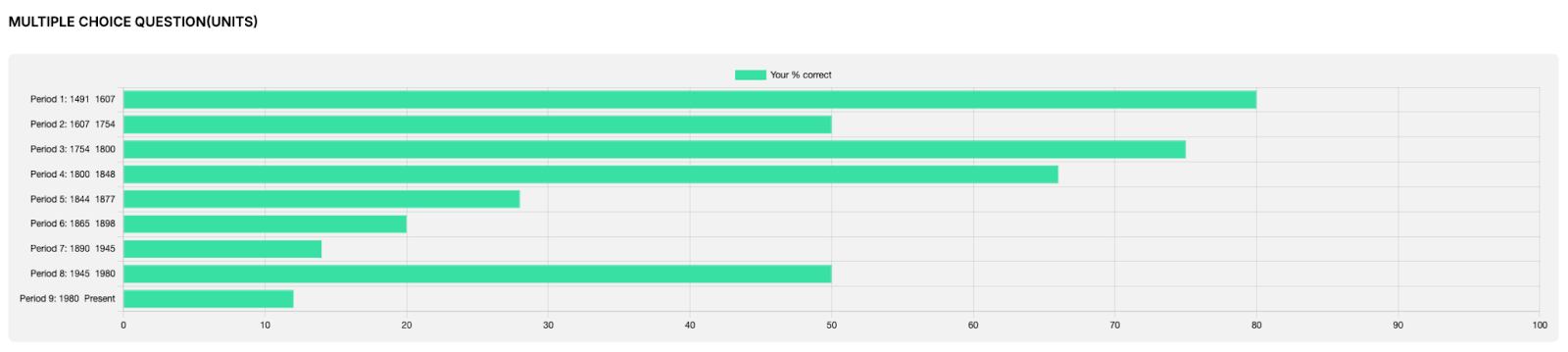

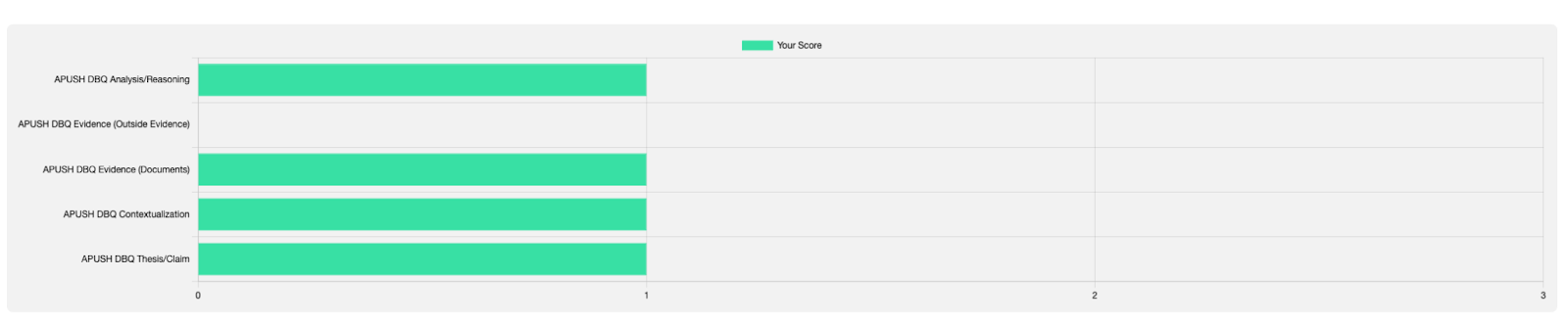

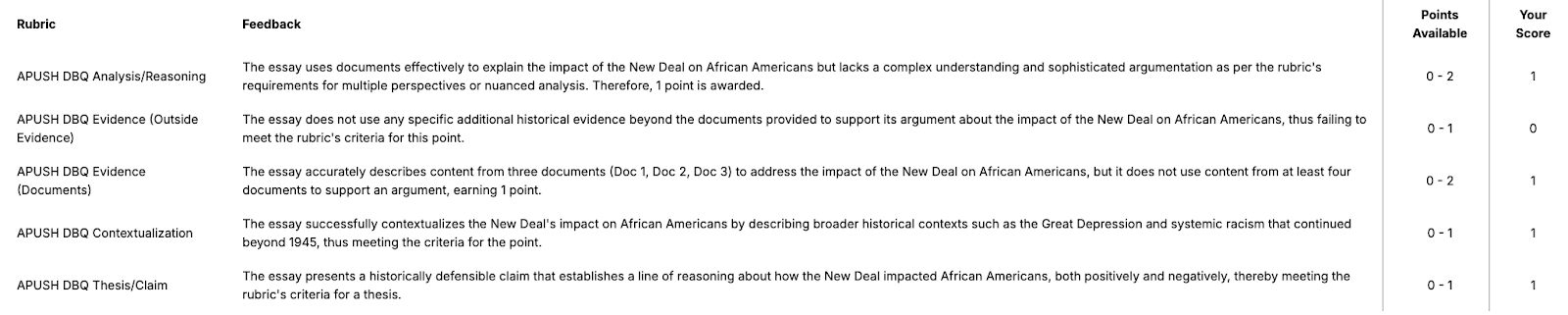

📣 Shout out to Miss Emily Reuter at Alliance College-Ready Gertz-Ressler High School in Los Angeles, CA for carving out the time for her students to prep for the AP exam through providing multiple practice exams.

📣 Shout out to Ms. Ali at Maya Angelou Schools in Washington, DC, for leaving no stone unturned when exploring ways to empower her students with the skills and dispositions they need for success.

📣 Shout out to Ms. Becca Schaeffer-Dombkowski at Highland High School in Highland, AR for giving her students who feel less comfortable in writing the opportunity to share their evidence-informed perspectives through socratic seminars in her class.

I have the privilege of working with many teachers throughout the country and the above examples are only scratching the surface of all the amazing work I get to witness in classrooms, department meetings, and PLCs. Civics may not be in the title of many of those classes, but rest assured, students are being equipped with the knowledge, skills, and dispositions to contribute to a flourishing democracy and thrive in an ever-changing world.

This Civic Learning Week, we are so grateful for all of you.