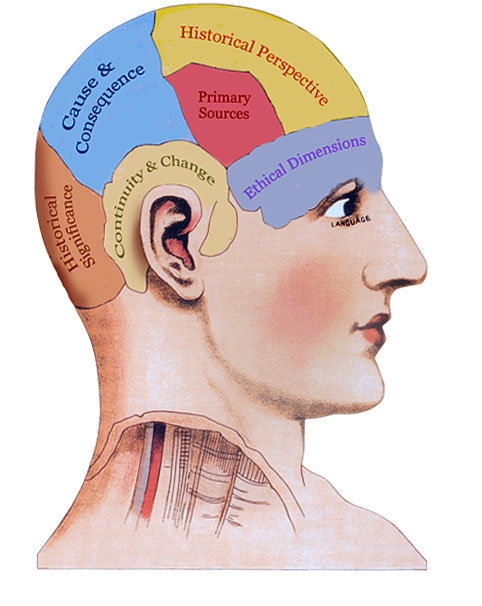

In the realm of historical thinking skills, I fear that analyzing historical significance is the most forgotten. We love to talk about causation, continuity and change over time, and contextualization, but historical significance (besides not conveniently beginning with a “c”) receives far less attention. What a shame.

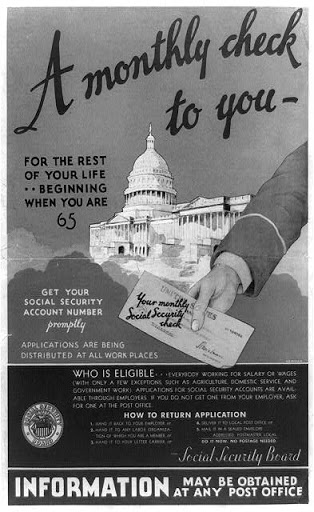

Canada’s Historical Thinking Project, on the other hand, lists it first on its page of historical concepts. We could learn a lot from our friends up north in this respect. The project admits that “Significance depends upon one’s perspective and purpose.” History, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. The project’s description elaborates that, “a historical person or event can acquire significance if we, the historians, can link it to larger trends and stories that reveal something important for us today.” Today, though, I want to extend its importance more broadly to Thinking Nation’s mission of cultivating thinking citizens.

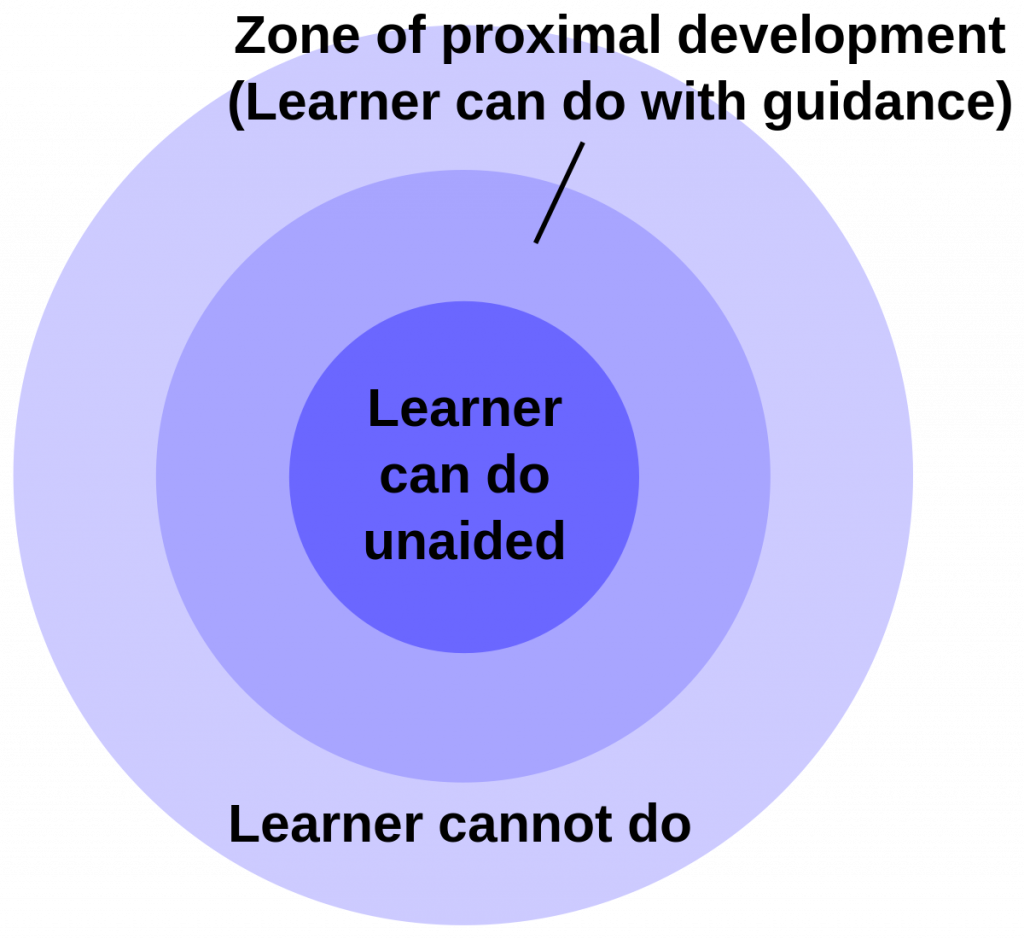

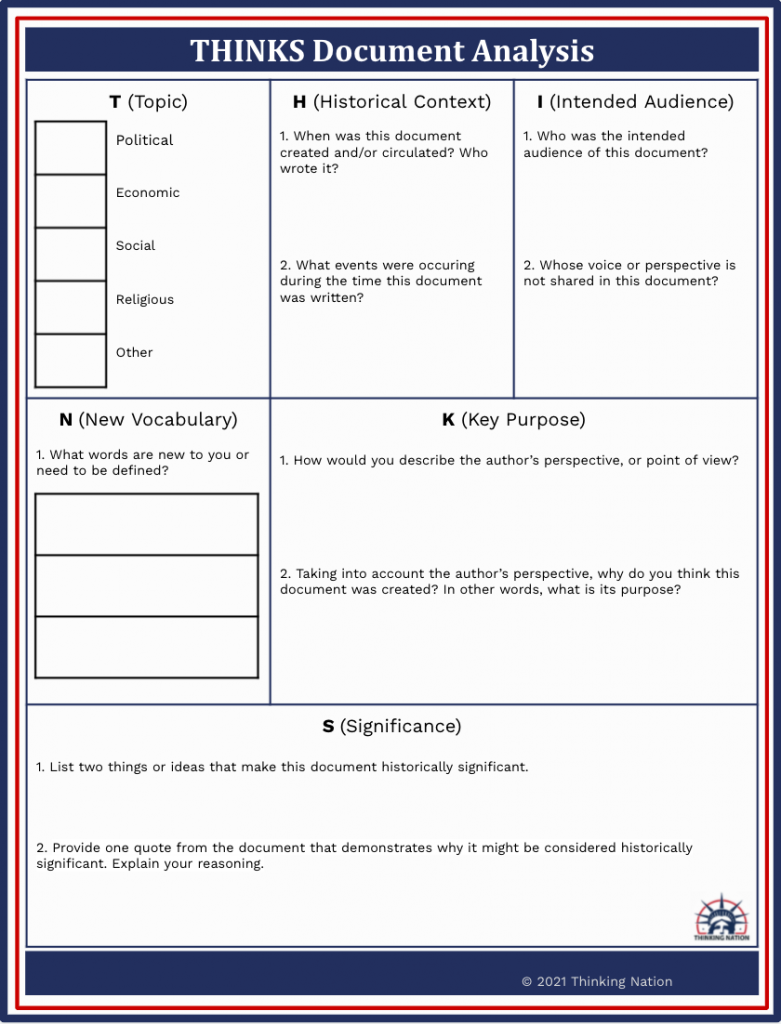

On all of our DBQs that focus on historical significance, we include this simple definition for students: “Thinking historically means identifying and exploring the reasons why historical people, places, events, or ideas are worth remembering; that is, their historical significance.” Exploring historical significance challenges students to consider the importance of historical events and people that they may not initially connect with. In essence, it is a tool that leads to historical empathy.

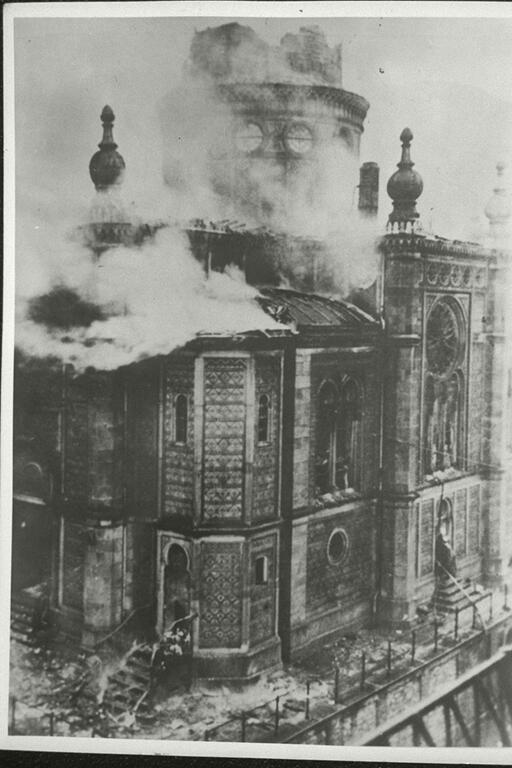

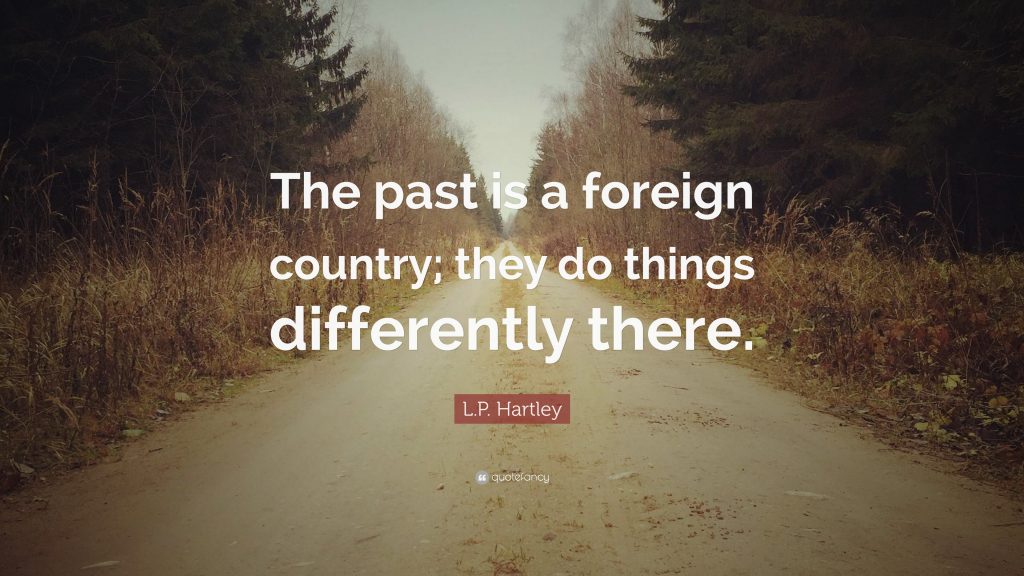

When we try to understand why something is historically significant, we are empathizing. We are trying to better understand past people, places, and events in a way that accurately reflects what happened. This type of understanding–of people not like us– is something our democracy desperately needs.

As we’ve argued before, the past does not need to be familiar to be relevant. Students who try to understand the significance of events can more easily humanize their subjects. This act of empathy is such a beautiful result of historical thinking that we must stress more in our classrooms. We don’t just want to cultivate historical thinkers. We want to cultivate thinking citizens. Citizens who make their neighborhoods, states, and country more understanding, inclusive, and kind. Teaching students to analyze historical significance can do a lot to help us get there.