If you’ve taught more than one semester before, you’ve experienced teaching in October. The honeymoon stage with the students is over. Behavior in the class, if things were not established in incredibly explicit terms, begins to be harder to manage. Students begin feel a little tired and perhaps even a little apathetic toward learning, wishing to be back on summer break. October is hard! Many people know that November 1st of my first year of teaching was my lowest point as an educator. I felt defeated and I quite literally questioned my choice of going into education. I was equally exhausted and perplexed.

These scenarios and reflections are not uncommon in education. Just talk to a teacher. With that being the case, though, what do we do? How do we set ourselves up for success despite the pitfalls that come in this month? How can we continue to set the foundation for a year of academic growth for our students?

Unfortunately, I don’t have a 5 point plan for success when teaching in October. I’m not sure one exists. But there are some important things we should consider and reflect on, especially as history teachers.

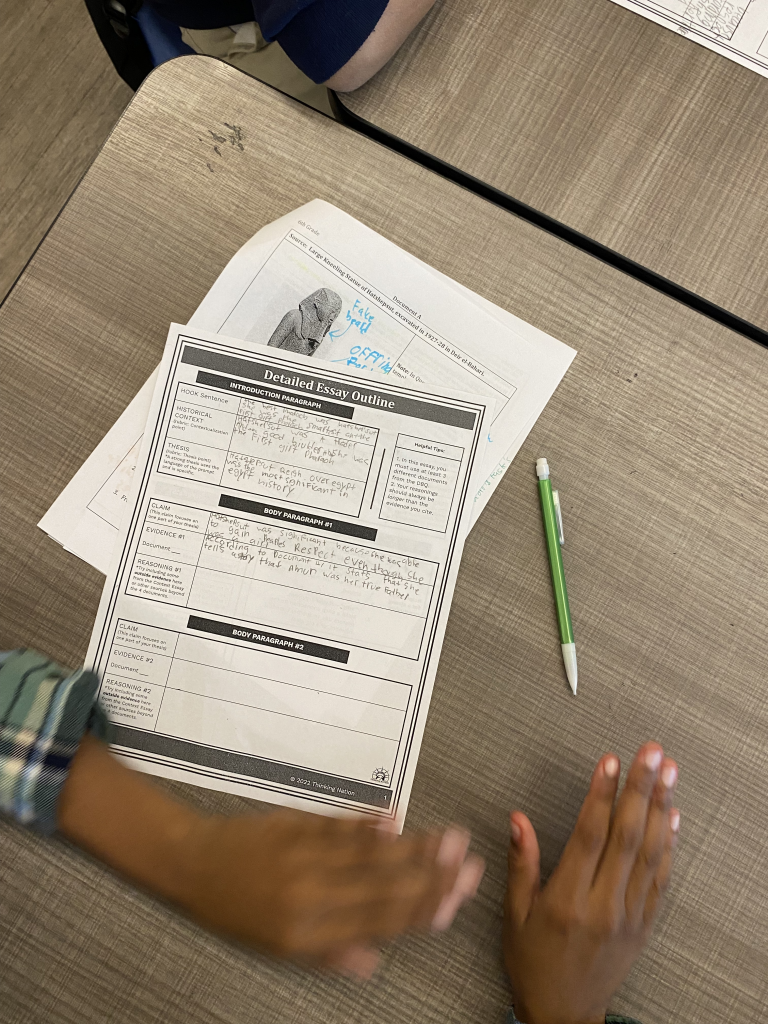

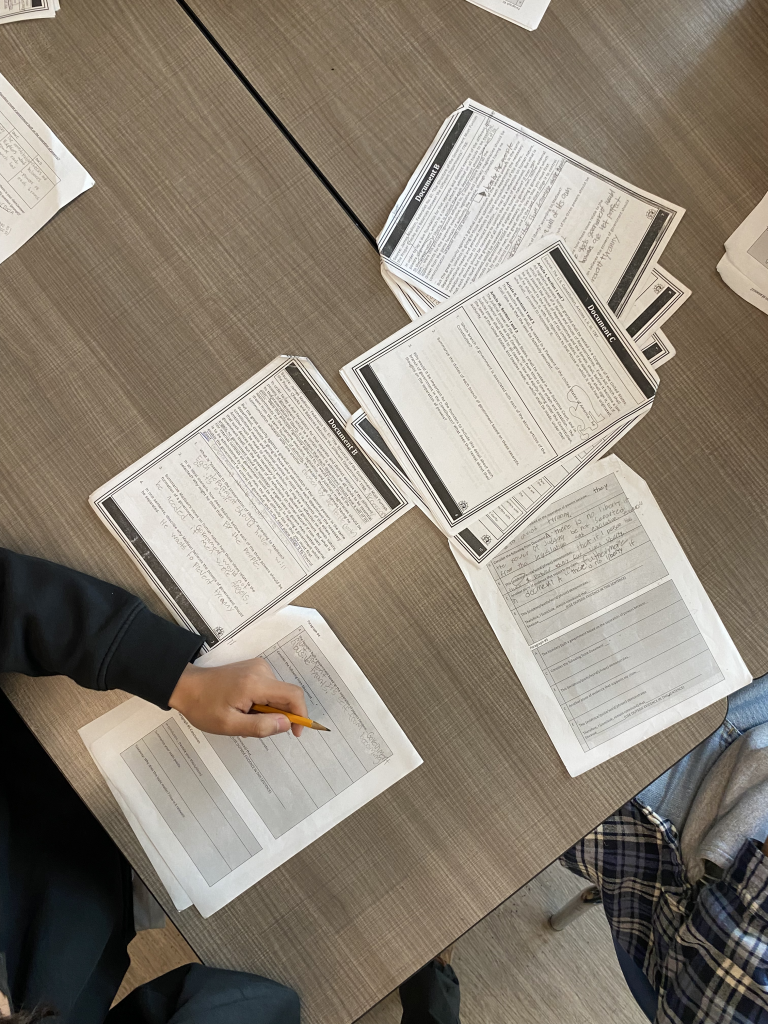

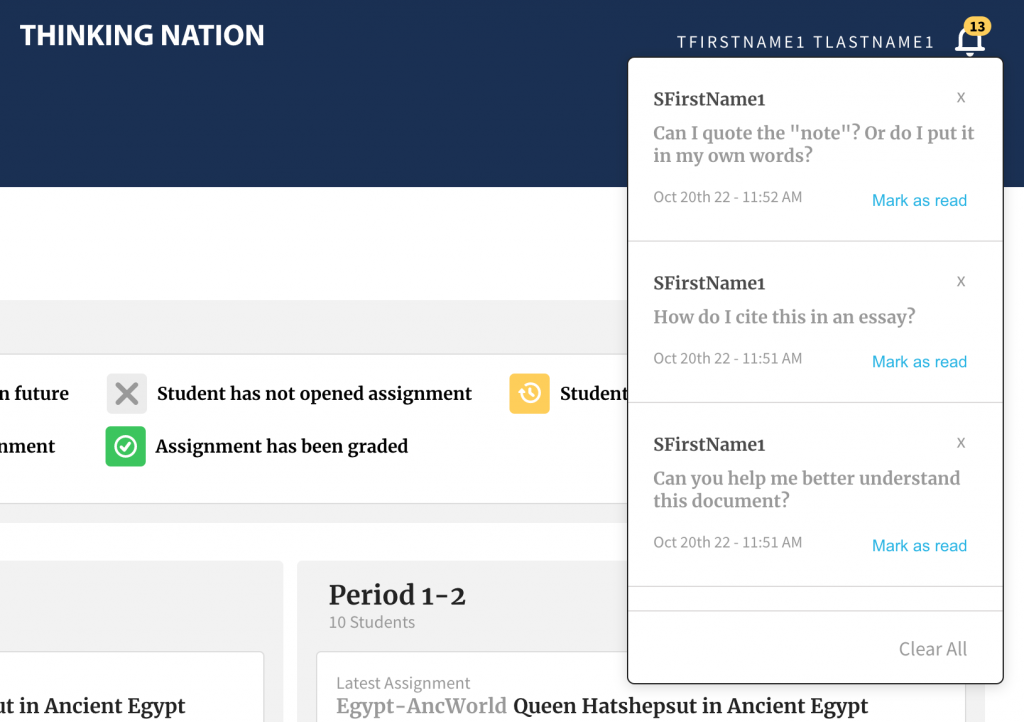

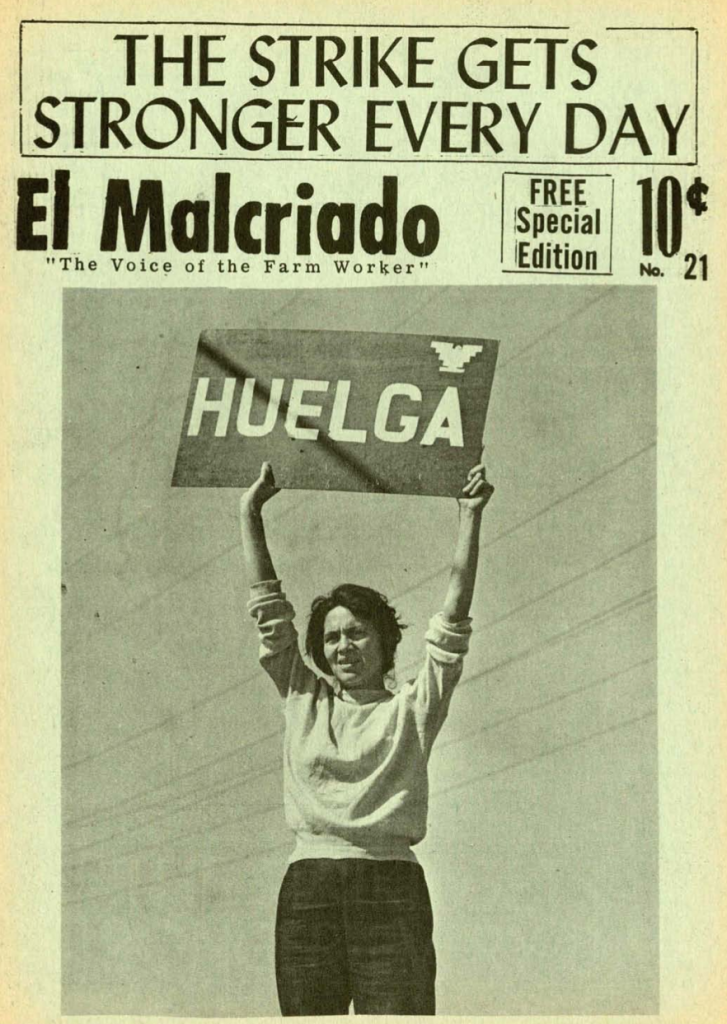

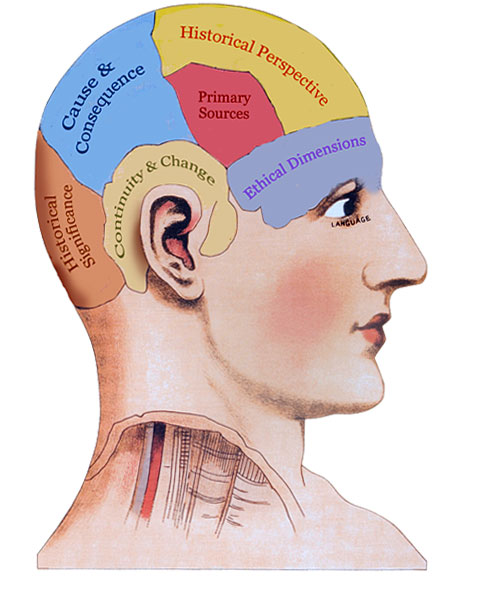

First, we must remind ourselves of our purpose as teachers. As this blog has emphasized time and again, our job is to teach students how to study the past. Teaching the past is not enough. History is bigger than a timeline. It’s a discipline of study. Creating routines in our classrooms around reading, analyzing, and writing about the past reminds students that they are in our classroom to become better thinkers, not better at recall. Reminding ourselves of this purpose (DAILY!) is critical for cementing our purpose as history teachers.

We also have to reset structures if they need to be reset. Do you see things that irritate you as a teacher but aren’t quite enough to call out? Call them out anyway. Set your behavioral standards in stone. Resetting is hard, but it is better in October than in January. Good, quality, historical thinking cannot happen in classrooms where management takes all of our energy.

The last thing worth considering, at least in this post, is to set a routine of historical thinking in your room. Make that word have daily resonance with your students. Introduce a new skill each week. Give concrete examples of it and adequate time to practice thinking that way. Have students write something argumentative, even if short, as often as possible. If they aren’t ready to do it on their own, do it with them! Students cannot do what they’ve never seen. Be a model of analysis. Doing heavy lifting for students at this point of the year is ok! Especially if you are giving them the framework to do that lifting on their own later in the year.

Teaching in October is hard. So many things are thrown at teachers. But, reminding ourselves of our purpose daily, resetting structures to create pathways to success, and embedding historical thinking into every lesson are important steps to take to make it a successful year of academic growth.