Thinking Nation Blog

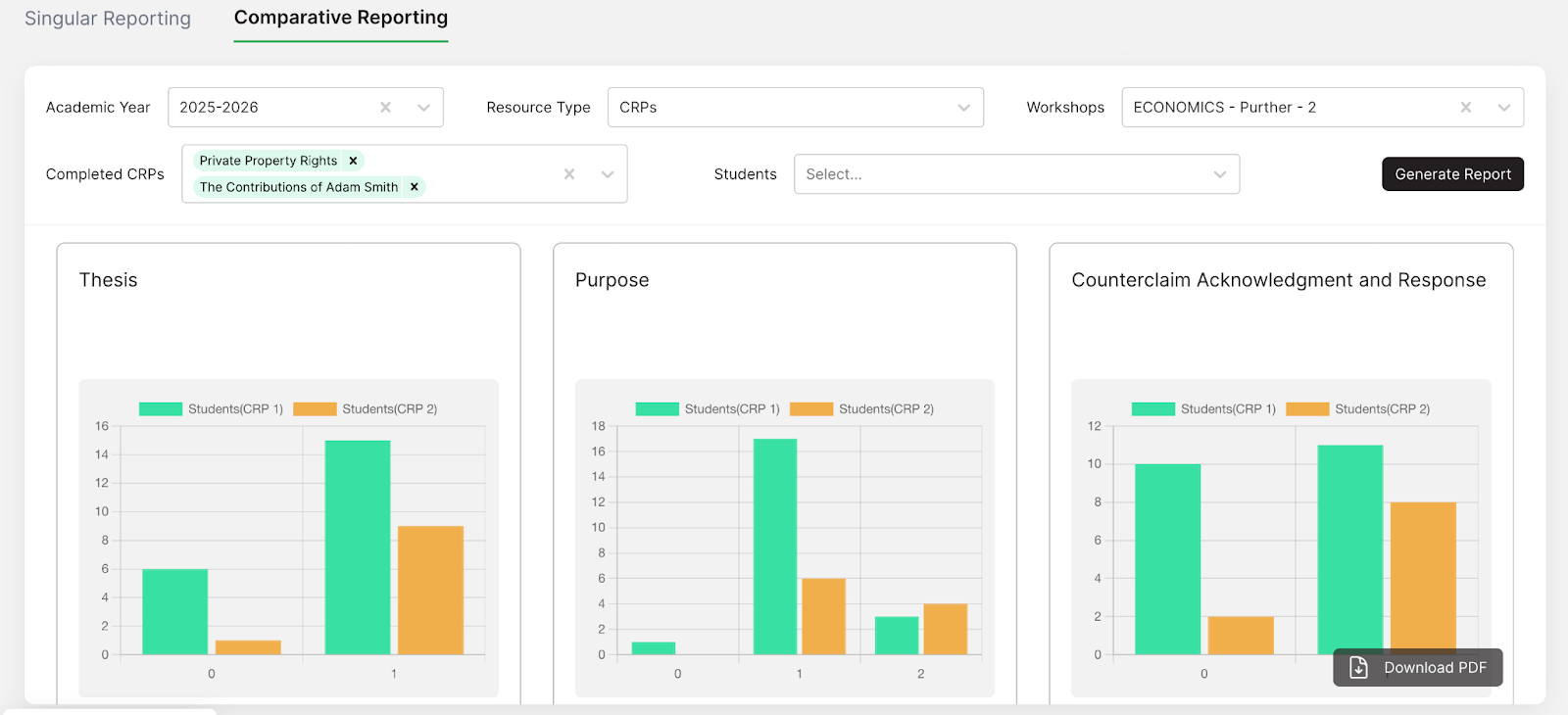

The New Minimum Standard: Data-Informed

If you’ve been in the same room as me more than once, you’ve probably ...

Partner Spotlight: Hamilton Heights MS - Arcadia, IN

Collaboration in Action: A Social Studies Team Setting the Standard

The New Minimum Standard: Rooted in Historical Thinking

Can you play soccer without a soccer ball? Can you have a dance withou...

-1.png)

The New Minimum Standard: Why Inquiry Matters and Supporting Student Questioning

History is a discipline, not a content. In my professional life, I mig...

Not Your Typical New Year’s Blog Post

Everywhere you turn right now, it’s “New Year, New You!” Fresh starts,...

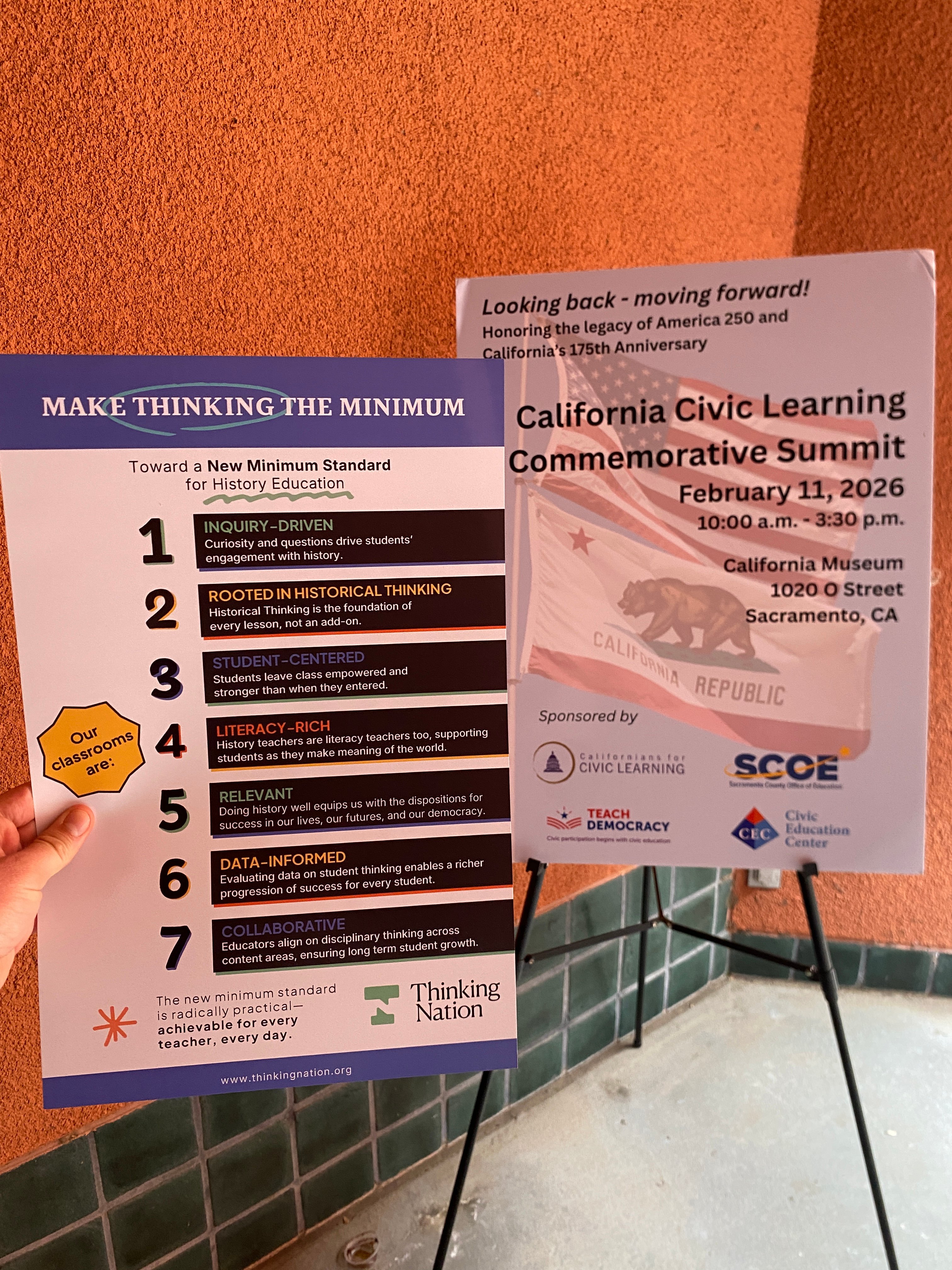

OPED: For the Sake of Democracy, We Need to Rethink How We Assess History in Schools

On December 2, The Fulcrum published my article on why we need to chan...

NCSS RECAP 2025

I’m almost fully recovered from an insanely busy time at the National ...

Cultivating Thinkers: Our 2024-2025 Impact Report

As we reflect on the past year, we are inspired by what happens when t...

Reflecting on Experience: A Year-End Guide for Teachers

There were a lot of things that went wrong during my first year of tea...

Happy Teacher Appreciation Week!

At Thinking Nation, we are so fortunate to work with such dedicated ed...

Recent Posts

- Why This New Minimum Standard Matters

- The New Minimum Standard: Data-Informed

- Partner Spotlight: Hamilton Heights MS - Arcadia, IN

- The New Minimum Standard: Rooted in Historical Thinking

- The New Minimum Standard: Why Inquiry Matters and Supporting Student Questioning

- Not Your Typical New Year’s Blog Post

- OPED: For the Sake of Democracy, We Need to Rethink How We Assess History in Schools

- NCSS RECAP 2025

- Cultivating Thinkers: Our 2024-2025 Impact Report

- Reflecting on Experience: A Year-End Guide for Teachers